JASON RHOADES

CREDITS

All images © The Estate of Jason Rhoades, Courtesy of the Estate of Jason Rhoades and Hauser & Wirth

Jonathan Griffin in conversation with Ingrid Schaffner for B.I. COLLECTION

In February 2024, Hauser & Wirth in Downtown Los Angeles opened an unusual exhibition. Parked in a large gallery were four cars, and not much else. Except for a handsome blue Ferrari, these were not obviously desirable classic sportscars: two were 90s Chevrolet sedans, and one was a faintly silly white microcar.

The exhibition was attributed to the Los Angeles-based artist Jason Rhoades, a mercurial figure who rose fast to international acclaim when he graduated from college in 1993, then died unexpectedly in 2006, aged 41. Rhoades is best known for his exuberant, gallery-busting installations of stuff, much of it bought in bulk, some of it culturally inflammatory (Native American dream-catchers, a Lego model of the Kaaba, neon slang words for female genitalia). Rhoades was an artist of excess, of provocation, and of unfiltered ambition.

“DRIVE,” as Hauser & Wirth’s yearlong programme of five exhibitions was called, was intended to redress some of the stereotypes and associations often attached to Rhoades and his work. Ingrid Schaffner, the programme’s curator, told me that she is weary of hearing people dismiss Rhoades as an overly macho, white “bro.” “DRIVE,” which focuses on Rhoades’ (typically masculine) fascination with cars, surprisingly reveals a more discursive, more thoughtful side of the sculptor.

Schaffner and I met at Hauser & Wirth, LA, to discuss cars, ambition, value, and what people have been getting wrong about Rhoades.

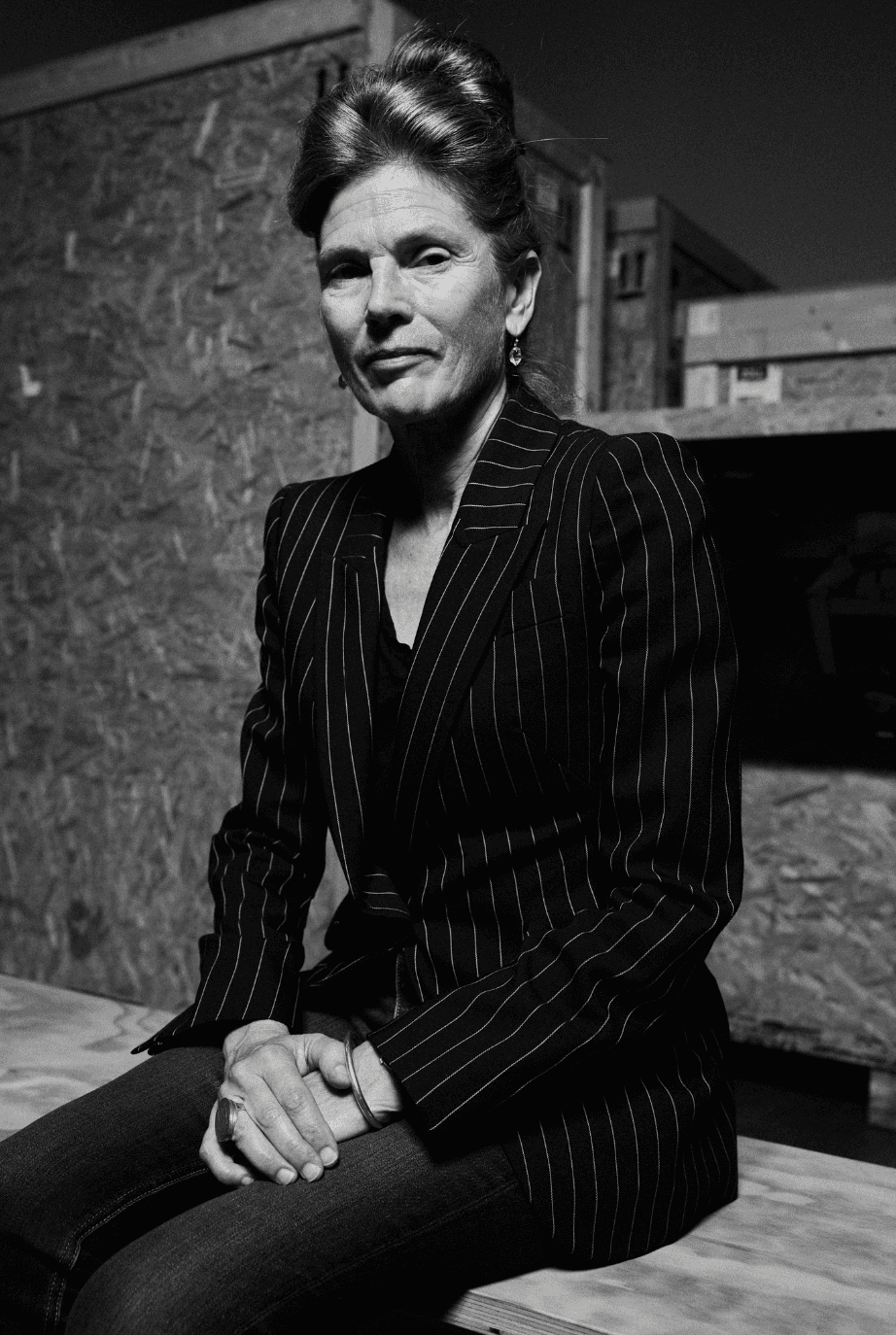

INGRID SCHAFFNER shot by Ellington Hammond

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

So, who was Jason Rhoades? How much of his work is autobiographical?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Well, Jason grew up in a rural, blue-collar town called Newcastle, in northern California. He was always messing around in garages and barns. He could drive a tractor. He could rope a steer. He had a prize-winning sheep, which he showed in the county fair. His mother Jackie was theatrical, and staged musicals in the family’s barn.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

We’re standing in front of a shed-like structure, loosely made from wood and plasterboard. It’s raised a foot or so off the ground, and I can see things stuffed underneath it and stashed on top. Inside, surrounded by all sorts of objects – from extension cords to offcuts of wood to tools and food made from aluminium foil – I can see what looks like a car engine.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

This installation is called Garage Renovation New York (CHERRY Makita) (1993). Rhoades made it immediately after he earned his art degree at UCLA, for the very first show at the new David Zwirner Gallery in New York, which opened on September 11th, 1993. That is a General Motors Chevrolet 350 V8 car engine, which Rhoades has repurposed to power a drill bit. Makita was the most popular brand of cordless drill. Their product liberated the DIY home builder – “All the power you need” was their slogan. And so Jason’s work would continue to play with ideas and actualities, tools, of power.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Is it functional?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

I don’t know how you start an engine without a key, but Jason knew, and according to David Zwirner he fired it up a couple of times during the exhibition. This exhaust pipe is real, and necessary.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Is that a book about Tutankhamen, on the desk?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Jason and his wife, the artist Rachel Khedoori, had travelled to Egypt where the treasures from Tutankhamen’s tomb – and the fact that it was trashed by robbers – made quite an impression.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

So this sculpture is describing something that is spoiled or defiled?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Or sacred, perhaps. It’s a garage, it’s a studio, it’s a tomb, it’s a crèche. If you follow the tomb metaphor, all these tools made of silver foil and pizzas cast in metal are things to sustain the boy king in the afterlife.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Rhoades saw himself as the boy king?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

The mechanic who occupied the garage was. You see that shoe, up on the roof? That’s part of the racing suit Jason wore in his final project at UCLA, Young Wight Grand Prix (1993). He made the suit, the track and the car, a kit car Ferrari that he turned into a Formula-One car by sticking a sculptural nose onto it. And he’s racing against himself – the last lap of graduate school before entering the professional art world. Naturally, he leaves a winner. That student self is stowed in the eaves of this garage. In Rhoades’s work, there’s always parts that we don’t have ready access to – that hold mystery.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

That’s a sculptural dynamic, but also a metaphor about selfhood and interpretation.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

He always holds something back. At the same time, his sculptures were meant to reward deep looking.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

The artist teases the possibility of self-revelation by hinting that there are things in the work that are both true and untrue. It cuts both ways.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

He’s fabricating a legend, I think, from the very beginning. Newcastle, where he was born, was near Sutter’s Mill, where gold was first discovered in California.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

So he grew up surrounded by the mythology of extreme wealth and self-made men.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

It was a boomtown. There was also plenty of bust. Rhoades had the mettle of American optimism that through hard work and determination things would pan out.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

As a blue-collar person entering the art world, perhaps there was a comparable phenomenon of high value (and potential personal wealth, and fame) combined with proletariat, everyday studio labour, comparable to garage tinkering and DIY.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

The idea of “work” gets a total workout in Rhoades’ work. He thought of his sculptures as being one continuous work of art, into which he was constantly ploughing ideas, materials, information, resources, money, opportunities, with the single-minded ambition of taking his work – and, with it, art more broadly – to the next level.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

It’s interesting to think about the notion of work in relation to the Readymade – the creative strategy invented by Marcel Duchamp, whereby just choosing an existing object and calling it art displaces the traditional labour of crafting a painting or sculpture. It’s really a kind of anti-labour. Maybe it’s intellectual labour, but it’s certainly the opposite of building a huge shed with a load of things inside. Rhoades used both strategies in his art – sculptures and installations made painstakingly by hand, and Readymade objects such as his cars. These approaches raise interesting problems to do with relative value.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

One thing I find very exciting about this work is what it’s saying to us as viewers, collectors, curators, institutions: “Value this!”

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Like a challenge.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

And it is a challenge! Materially, there’s just so much to Rhoades’ work. Organic substances that spoil. Mechanics that break. Technologies that go obsolescent. Things that just crumple. For that work to exist over time, it sets a whole new bar for the field of conservation! Traditional painting and sculpture is pretty meek in its demands, relatively speaking.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Do you think he was deliberately making it as challenging as possible to preserve this stuff?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Absolutely. A work he made for the 1995 Whitney Biennial, titled My Brother/Brancuzi, included a donut machine, which produced endless columns of greasy, fresh, fragrant donuts as part of the installation. Another artist he greatly admired, besides Constantin Brancusi, was Dieter Roth, who made work with chocolate and cheese, and whose concept of the total work of art was very impactful on him.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

But ultimately, he did want his work to be valued?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Again, absolutely. On a small but meaningful note, Rhoades’s instructions for the installation of his work always began with: “Make sure floor is swept and the space is clean.” He knew people could see his work as chaotic or random. But it was sculpture, and he wanted it to be treated with the same consideration as say, a Donald Judd.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

What challenges do cars pose for conservators? Rhoades’ first work that included a car was the Yellow Fiero, which he drove and used.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

My understanding is that he acquired it as a material for another one of his early sculptures, Swedish Erotica and Fiero Parts (1994). It was a large installation modelled on the idea of an IKEA store. Rhoades was interested how the Pontiac Fiero was an American attempt to make a European-style sports car. It has something to do with the Fiero having a mid-body engine, as well as its styling. The fact that the Fiero had this monocoque shell that you could change out – you could give it a different front end, you could give it different doors – meant that it also had this self-assembly quality that goes with the IKEA concept.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Then, of course, Rhoades’ interest in in the relationship between Europe and America is to do with the history of Modernism. How the nexus of Modern art moved from Paris to New York, between the World Wars. That journey of cultural capital from Europe to America is, in a sense, about the democratization of culture as well. The Pontiac is much cheaper than the European sports cars that it was influenced by. Through American capitalism, everything becomes affordable and accessible to the masses.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Jason turned the Yellow Fiero into a Ferrari just by gluing a Ferrari emblem on the nose and drawing a stallion on the steering wheel. It was a pretty classy Duchampian move, if you consider that Marcel Duchamp turned a urinal into a work of art in a similar way.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

So undermining this apparent self-aggrandization, there’s a pathos there.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

There’s always a lot of levelling going in Rhoades’ work, which roped in everything around him: class, craft, the internet, art history, the market, cars, and so on. It’s very unimaginative, I think, to critique Rhoades’ work as being nothing more than “bro.” I don’t know if it’s a send-up of masculinity, exactly, but this is not macho work. If anything, it allows for the ridiculousness of sheer testosterone as a drive. Abjection was a key term for Rhoades. And so was humour.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

The artists he was most influenced by, like his former professor Paul McCarthy, the Viennese Actionists or Dieter Roth, all in a sense debased themselves through their work. McCarthy’s work partly came out of 1970s Feminism, which is not often remembered – his performances were concerned with the abjection of the classically heroic male body.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

I’ve always identified with this kind of work as a feminist who doesn’t believe that an artist has to identify as a woman to mess with the patriarchy.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

What were some other reasons that Rhoades was first interested in cars?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

For Jason, the car was not just a vehicle but an artistic tool – for making sculpture, for drifting along and being in your own head, for being in dialogue with other people about your work and creating discourse. In the first exhibition of “DRIVE,” we presented a terrific video of Jason in the Caprice being interviewed by the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, who could barely get a word in edgewise. It’s filmed from the back seat, so you really feel like you’re in the car too, driving around Los Angeles, while Jason is enthusiastically explaining his “Car Projects.” No matter how vast his sculptures would become, he always created space in his work to be with just one or two other people. The intimacy of the car was important for him.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

The first exhibition in this series essentially just featured four cars parked in the gallery. The earliest being the Chevrolet Caprice, from 1996, then the Chevrolet Impala from 1998, the Ferrari from 1998 and the Ligier Microcar. Can we talk about what all these cars are, and what they mean? Was the Caprice a former police car?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

It was probably used by an undercover detective. There’s a sticker over the steering wheel that reads: “USE OVERDRIVE IN HIGHSPEED PURSUITS.” Jason bought it, second-hand, in Carmel, California, where – he liked to point out – Clint Eastwood was the mayor. So the car also had “Dirty Harry” associations. Rhoades acquired the car after he was invited by the curator Nicolas Bourriaud to participate in an exhibition in a museum in Bordeaux which was – coincidentally – titled “Traffic,” though it had nothing to do with cars.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Bourriaud is famous for theorizing in the 1990s the artistic tendency that he called Relational Aesthetics, in which the essential medium of the artwork is social relations.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Right. In his invitation to artists, Bourriaud wrote that the exhibition would be all about the energy they bring in relation to the institution and one another. Jason responds by inviting the museum to enter into a partnership with him to buy the Caprice. He reasons that as an LA artist, he spends so much time in the car it is effectively an extension of his studio. But once they helped him buy the car, they couldn't afford to bring his “studio” to Bordeaux. My understanding is that, instead, Jason provided the exhibition with photographs and other ephemeral things that he made while driving around in the Caprice Auto Project, as it was titled.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

So it became his personal car?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

According to the contract Rhoades drew up with the museum (which was part of the work), it was a 49/51% split that left him with the majority interest in the Caprice. So it became his daily drive. Soon after “Traffic,” the curator Joshua Decter invited Jason to participate in “a/drift,” an exhibition that looked at how the boundaries between art, pop music, fashion, film and television were all blending together. Jason’s proposition took that drift even further, I suppose, by proposing that the museum pay for a garage tune-up and oil change for the Caprice. The sculpture, titled 3,000 miles or you can sit down, consisted of the bucket of used oil, the old spark plugs and the mechanic’s receipt. It was one of the several works that have been “rediscovered” in the process of organizing “DRIVE,” which has been as much a research project as an exhibition. The cars themselves were retrieved from a storage facility in the Mojave Desert. For me as curator, it’s been extremely rewarding to work closely with gallery colleagues to bring this work not only to light, but to life.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

For this work, and these cars, to come to life, though, that means being institutionalized.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Right, not putting them on the road but handling them like works of art.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

What was involved, conservation-wise, to make these cars ready for exhibition?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

This was outside the gallery’s usual realm of expertise. We turned to Juan Carlos Guerrero, whose business prepares cars for auctions and shows. He detailed every inch of Rhoades’s car sculptures, which were filthy, their tires were flat, there were infestation issues. They’d been sitting in storage for decades.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Are they drivable now? Or will they never be driven again?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

To show the cars in the gallery, all the fluids had to be drained. For now, their driving days are done. As Rhoades said, each car was a vehicle for its own project. When the project ended, the car stopped and became a sculpture.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

What drew him to the Chevy Impala?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

The Impala and the Caprice were both what Rhoades called “bubble cars,” these kinds of classic American rides where you feel like you’re just floating along. The Impala was Chevy’s last-ditch effort to make a sporty, sexy car at a time when the car industry really needed to rethink its game because of the rising price of oil. Just when things should be getting lighter, more efficient, they made this giant sexy beast of a car.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

But it was fast? A fast comfortable family car?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Someone told me that, stereotypically, the Caprice – the cop car – would have been chasing the Impala.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

So Jason bought the Impala and had it shipped to an exhibition at Kunsthaus Zurich?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

The IMPALA (International Museum Project About Leaving and Arriving) was created for an exhibition of emerging artists at Kunsthaus Zurich, in 1998. The car was parked on the plaza beside outdoor sculptures by other artists, where it also functioned as a little museum on wheels. There was Chanel 22 in the glovebox, a Readymade sculpture by Sylvie Fleury. Because Rhoades contended that the passenger seat is a feminine space, he thought it should have a nice smell. In the trunk, he displayed another fragrant artwork: an homage to Dieter Roth’s Staple Cheese (A Race), from 1970, which had consisted of 37 suitcases filled with rotting cheese.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

I read that Rhoades would drive the car when he was in Switzerland, during the run of the show. And he lent the keys to Paul McCarthy too, when he visited Zurich with his family.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

The deal was that other artists could use the car as long as they left behind their aura – and their trash. Paul recalls that the car was pretty much full up with McDonald’s wrappers by the time he was done driving it around Switzerland. Rhoades was exploring the potential of a car to be a time capsule.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

From these big Chevys and the Pontiac, how did he come to acquire an actual Ferrari?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

This was another very transactional “Car Project.” A Zurich-based collector owned a beautiful blue Ferrari 328 GTS. And Rhoades proposed to her that now the Chevy Caprice was a work of art, it was worth as much as a Ferrari. Totally in the spirt of his work, she made the trade and a new deal: he could keep the Ferrari as long as he drove her around whenever she was in LA. The Ferrari is the vehicle of ambition – when you have a Ferrari you’re next level, right? Especially in LA, when you show up at the valet.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

As an artist, you’re conspicuous.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

It’s a little gauche for a young artist to have this car, no? It was Jason’s showboat.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Was the Ferrari a sculpture too?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Yes. The way Rhoades got the Ferrari from Zurich to Los Angeles was by making it part of his installation for the 1999 Venice Biennale, which then was obligated to ship the work back to the artist. Jason also made a separate piece using the Ferrari’s luxurious custom luggage, which he filled up with porn magazines. Hey, driving a Ferrari is sexy. He was also teasing out the connections between Modernism, sex and humour. He was influenced by Marcel Duchamp and also Francis Picabia, whose work dealt with similar themes. He acquired the Ligier Microcar in Nice, where Picabia lived, and modified it so that the passenger seat faced the back. It became a “conversation car,” and he imagined Duchamp and Picabia in endless tete á tete in this little French car.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

Picabia was a kind of privileged playboy, who raced cars and introduced kitsch and erotica into his painting.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

In New York right now, at the final iteration of the “DRIVE” exhibitions, we have a sculpture by Rhoades titled Fucking Picabia Cars with Ejection Seat (1997/2000). It is an abstract representation of two cars that Picabia owned, basically getting it on. You can glean this from the pictures of Picabia’s cars that are glued onto the sculpture! Rhoades requested that wherever possible, the sculpture should be exhibited alongside work by Picabia; we were able to present three paintings by him in the New York show.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

That exhibition is also the only iteration of “DRIVE” that includes Rhoades’ Yellow Fiero.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

The sculpture belongs to David and Monica Zwirner and its inclusion in New York represents the first time that the whole fleet has been shown together. The Fiero really stands apart. It is less ready-made. Rhoades spray-painted it yellow from a can. It has this weird matte finish to it. It’s dirty in this really nice tactile way.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

How much was Rhoades involved in ironic art historical reference, and how much was his acknowledgement of artistic precedents sincere and admiring?

INGRID SCHAFFNER

I question more and more my assumption that this work is ironic. I mean, for those of us who came up in the 90s, everything was ironic. Now I see so much sincerity in it. Rhoades unabashedly believed in art’s ability to perform, to work, to hold meaning and mystery, creativity, and drive. Other artists, especially, find so much energy in his work’s sense of freedom and permission.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

His art can be very touching.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

I myself was surprised at how much energy I felt. Putting cars in the gallery sounds stupidly simple, but their presence was truly uncanny. They felt like something out of another time. We don’t see cars like that anymore. I doubt Rhoades was anticipating an age in which we would need to get past the combustible engine, but these cars appear like dinosaurs, driving themselves to extinction.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

It’s all the more poignant because Rhoades died. Cars are intimate spaces, and his absence is palpable.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

He’s not there.

JONATHAN GRIFFIN

“DRIVE” is clearly a huge endeavour for Hauser & Wirth – a year-long series of archival, research-based exhibitions, in two cities. And it’s not an obviously commercial show – as I understand it, the cars are not for sale.

INGRID SCHAFFNER

Iwan and Manuela Wirth and Ursula Hauser were very close to Jason. To some degree, the reason there’s even a gallery here in Los Angeles is due to him. They all met in Europe, where Rhoades, like many LA artists including Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, had his biggest early reception. Iwan says that whenever they came to town, Jason would meet them at the hotel and drive them over to a classic car dealership in West Hollywood to kick the tires for a bit before heading off for studio visits. Last year, Hauser & Wirth opened its second LA space in that same building. Jason’s very much part of the DNA of this place. “DRIVE” is a commitment to Rhoades and his legacy, and to that friendship.